How Should a Christian View Israel: Part Two

By Eric Chabot, CJF Ministries Midwest Representative

This is the second post in our series on “How Should a Christian View Israel? (Part One is here)

As I already mentioned, I will expand on R. Kendall’s Soulen’s The God of Israel and Christian Theology which has shown the long history of supersessionism in Church history. Soulen, Professor of Systematic Theology at Wesley Theological Seminary, Washington DC. has written on the standard Christian “canonical narrative”—i.e., our view of the Bible’s overarching narrative framework—in such a way that avoids supersessionism and consequently is more coherent. Soulen identifies three kinds of supersessionism: (1) economic supersessionism, in which Israel’s obsolescence after the coming of the Messiah is a key element of the canonical narrative, (2) punitive supersessionism, in which God abrogates his covenant with Israel as a punishment for their rejection of Jesus, and (3) structural supersessionism, in which Israel’s special identity as God’s people is simply not an essential element of the “foreground” structure of the canonical narrative itself. Soulen sees structural supersessionism as the most problematic form of supersessionism, because it is the most deep-rooted. He identifies structural supersessionism in the “standard model” of the canonical narrative, which has held sway throughout much of the history of the Christian church. This standard model is structured by four main movements: creation, fall, Christ’s incarnation and the church, and the final consummation. In this standard model, God’s dealings with Israel are seen merely as a prefigurement of his dealings with the world through Christ. Thus, the Hebrew Scriptures are only confirmatory; they are not logically necessary for the narrative (see Lionel Windsor’s Reading Ephesians and Colossians after Supersessionism: Christ’s Mission through Israel to the Nations (New Testament after Supersessionism Book 2)

Structural Supersessionism

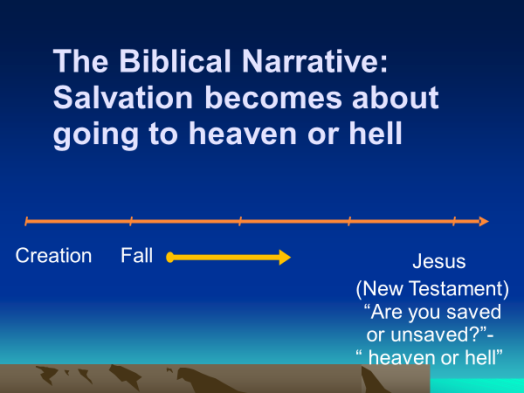

We just noted that “structural supersessionism” says Israel’s special identity as God’s people is simply not an essential element of the “foreground” structure of the canonical narrative itself. There has been a slew of books that attempt to help readers understand the grand narrative of the Bible. Books such as Living God’s Word: Discovering Our Place in the Great Story of Scripture, by J. Scott Duvall and J. Daniel Hay, or The Mission of God: Unlocking the Bible’s Grand Narrative by Christopher Wright are just a few of them. There is no doubt that once Christianity became a ‘separate’ religion outside of the Jewish world, one of the primary ways it began to define it’s belief system was through the use of creeds and confessions. It is noteworthy that the two greatest creeds, the Apostles’ and Nicene, jump from creation and fall to redemption through Jesus without even mentioning the history and people of Israel. I will offer two pictures to show the difference.

Almost every Christian and almost every church has recited the Apostles Creed. I am not against this. But let me ask you a question: If you read this creed, how much would you find out about the humanity of Jesus? While there is a mentioning of his death under Pilate and his burial as well, would you ever read this and realize Jesus was Jewish or that he is Israel’s Messiah? “Messiah” is directly related to the Davidic King in Jewish tradition (2 Sam 7:14; Ps 2:2, 7; 89:19-21, 26-27; Psalms of Solomon 17.32). Paul explicates this gospel “regarding his Son, who as to his earthly life was a descendant of David, and who through the Spirit of holiness was appointed the Son of God in power by his resurrection from the dead” (Rom 1:3-4). Here is the creed:

“I believe in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Only Begotten Son of God, born of the Father before all ages. God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, not made, consubstantial with the Father; through him all things were made. For us men and for our salvation he came down from heaven, and by the Holy Spirit was incarnate of the Virgin Mary, and became man. For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate, he suffered death and was buried, and rose again on the third day in accordance with the Scriptures. He ascended into heaven and is seated at the right hand of the Father. He will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead.”

While the Apostles creed is helpful to some, it really leaves out quite a bit. Anyone who reads it probably won’t walk away seeing any historical connection between Jesus and Israel. It leads me to this pertinent comment by Anthony Saldarini:

“Does Jesus the Jew—as a Jew—have any impact on Christian theology and on Jewish-Christian relations? . . . To wrench Jesus out of his Jewish world destroys Jesus and destroys Christianity, the religion that grew out of his teachings. Even Jesus’ most familiar role as Christ is a Jewish role. If Christians leave the concrete realities of Jesus’ life and of the history of Israel in favor of a mythic, universal, spiritual Jesus and an otherworldly kingdom of God, they deny their origins in Israel, their history, and the God who loved and protected Israel and the church. They cease to interpret the actual Jesus sent by God and remake him in their own image and likeness. The dangers are obvious. If Christians violently wrench Jesus out of his natural, ethnic and historical place within the people of Israel, they open the way to doing equal violence to Israel, the place and people of Jesus.”- A. Saldarini, “What Price the Uniqueness of Jesus?” Bible Review, June 1999: 17. Print.

In this picture, we see a more comprehensive picture of the biblical narrative:

The Problem of the Old Testament/New Testament Divide

The other problem with structural supersessionism is it can lead to an unnecessary divide between both Testaments. We can tend to forget there was no New Testament at the time of Jesus. Paul stated: “All scripture is given by the inspiration of God and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness: that the man of God may be perfect, thoroughly furnished unto all good works” (2 Timothy 3:16-17). Here “Scripture” (graphē) must refer to the Old Testament written Scripture, for that is what the word graphē refers to in every one of its fifty-one occurrences in the New Testament.

As Walter Kaiser states so clearly:

“God never intended that the two testaments should result in two separate religions: Judaism and Christianity. The Tanach (= OT) was meant to lead directly into the so-called New Testament and thus be the continuation of one plan from creation to consummation. When the divine promise-plan of God is ruptured and divided into two distinct parts, with the climax triumphing over the earlier revelation, then we have introduced a division where God had revealed the fulfillment of what he had revealed in earlier texts! Therefore, we must investigate further how this disparity appeared among the people of God”- Walter Kaiser, Jewish Christianity: Why Believing Jews and Gentiles Parted Ways in the Early Church

N.T Wright’s Corrective?

N.T. Wright is one of the most popular New Testament theologians today. A ways back, he wrote a popular book called “Surprised by Hope: Rethinking Heaven, the Resurrection, and the Mission of the Church. In this book, he rightly noted that Christians have forgotten that the final destination for the Christian is not heaven. But instead, salvation in the Bible is not the deliverance from the body, which is the prison of the soul. The believer’s final destination is not heaven, but it is the new heavens and new earth- complete with a resurrection body. Wright notes that while heaven is wonderful, resurrection is even better. Thus, as Wright says, resurrection is “life after life- after- death.” With this corrective, many Christians now realize they will eventually be on a renewed earth. With Wright’s corrective, a slew of books has emphasized that God has called humans to be priests and stewards of the physical environment of the earth, and not to be fixated with our souls that are hopefully on a journey to a disembodied heaven.

But, the question becomes the following: if God’s covenant with humanity eventually will be finalized on a renewed earth, are there geographical boundaries of any kind? And if so, does Israel exist as a nation and does the land called ‘Israel’ exist? I have come across more than enough Christians who say there is no purpose with the land of Israel. Thus, when Jesus came, the land has no present nor future significance in the mind of God. It is no more different than Africa, Russia, or any place else. But for those that have written Israel out of the canonical narrative, where is Israel in the new heavens and new earth? Rev 21: 1 discusses the new heaven and earth (also see Isa. 65:17–25; 66:22–23; 2 Pet. 12-13). But if the new creation has a place for the earth, and especially for resurrected human life living under the lordship of the Messiah, what about the political landscape of the new creation (Rev. 21: 22-22:4)? What tends to be forgotten is the Bible has always been a story of God, Israel, and the nations. The words “goyim” and “ethnos” refer to “peoples” or “nations” and are applied to both Israelites and non-Israelites in the Bible. In the eschaton, Israel is still in the picture along with the nations. You can’t have one without the other. After all, where does Jesus come back to? California? Russia? Or Jerusalem? The basic geography will remain so that Israel and Jerusalem will retain their distinctive prominence (Zech 14:8–11; Matt 19:28). Hence the heavens and the Earth will not be brand new but renewed.

Subscribe

Receive email updates when we post a new article by subscribing.

Categories

- Eric Chabot 71 entries

- Gary Hedrick 125 entries

Recent Posts

- What Does It Mean to Say Jesus is "The Son of God?"

- If God forbids human sacrifice in the Old Testament, how does the sacrifice of Jesus make sense?

- Why My Favorite Question for College Students is “Does God Exist?”

- Jewish scholar Michael S. Kogan on the uniqueness of Jesus’s messianic movement

- “Do the Miracles of Jesus Prove Messianic Status?”

Tagged

No tags